This is the full article from 1981:

POETRY IN ENGLAND TODAY

Statistically, poetry is flourishing in England today. Some two thousand poets publish their work in nearly two hundred little magazines, of which about fifty are well-produced and appear regularly. Over two hundred small presses publish books and pamphlets, from the cheap editions of the aptly named Shabby Press to the professional output of the Carcanet New Press, which competes with traditional publishing houses in size and quality. Nearly three hundred poetry societies, groups, clubs and reading circles function under the aegis of Regional Arts Associations and with the co-operation of the National Poetry Secretariat, which maintains files on over a thousand poets and helps to arrange readings. Large and well-organised poetry festivals are held regularly, and a visitor to any important English town can usually find poetry readings to attend.

But these statistics give a false picture. Other equally salient facts can be set against them: apart from thirty specialist bookshops (mostly in London) it is difficult to buy a volume of contemporary poetry in England other than those of half a dozen "Big Name" poets. Gavin Ewart has poignantly ridiculed this situation in a poem entitled 'In a London Bookshop':

There's a Scots poet called Dunbar -

they looked at me as from afar -

he wrote love poems, and divine

a master of the lovely line -

they looked askance, they looked as though

they didn't really want to know —

he knew the Court, the field, the meadow,

‘Twa mariit Wemen and the Wedo’,

satires and dirges, never loth,

he used his genius on them both -

they pursed their lips in noble scorn -

among the finest ever born,

he was by far superior to

the poets sold in stacks by you -

they spoke as proud as pigs in bran:

We’ve never heard of such a man.

This would be even more effective in the case of reader going to the same shop for one of the Gavin Ewart’s books.

Then, on the scanty evidence available, such as Norman Hiddens survey of the readership of his magazine New Poetry (The State of Poetry Today, The Workshop Press Ltd, 1978), the audience for this mass of poetry wouldappear to be dangerously circumscribed, almost incestuous, consisting mainly of poets, academics and school-teachers.

This survey also emphasises the difficulty of making accurate critical assessments of contemporaries: 366 respondents managed to cite 194 different candidates to place among the “best five living British poets". But disagreement candidates seems to lie in the third, fourth and fifth choices, where some idiosyncrasy or passing whim might be allowed to influence judgement, for a very small group of poets dominated the choices. Ted Hughes was mentioned 169 times and Philip Larkin 144 times. Other names with more than twenty mentions were Seamus Heaney, R.S. Thomas, Robert Graves, Charles Causeley, John Betjemen, Thom Gunn, Kathleen Raine, Roy Fuller, Brian Patten Vernon Scannell, Dannie Abse and Peter Redgrove. Although the sample was small, and might differ in details with the readership of another similar magazine, it produces no surprises. More or less the same names would cone up however one shuffled the pack.

Where are the other poets? What qualities and surprises lie at the centre of this confusion? If we look in from the outside, ignoring, because we cannot feel, the cliques, jealousies and factional squabbles (which are so fierce that one can read parallel runs of several magazines without being made aware that they are indeed contemporaneous) what shall we find?

Good work is being produced over a very wide spectrum, notwithstanding the periodic splenetic outbursts of older poets against the present situation (see, for example, John Wain in his Professing Poetry, Penguin, 1978, especially p. 29; and Geoffrey Grigson's grumble in the Times Literary Supplement for February 8th 1980). On the one hand, there is poetry proclaiming affiliation with traditional values, which Julian Symons usefully defined recently as "language and verse forms acknowledging debt to earlier poetry written in English (see TLS for January 1st, 1980; also Neil Powell's article ‘What is Traditional in Poetry?’ in Poetry National Review 2 (1977), (pp. 31-7). For instance, this short poem by Douglas Dunn, ‘Glasgow Schoolboys, Running Backwards’, vaunts three lines of perfect iambic pentameter, rhyme and transparent meaning as its virtues:

High wind . . . They turn their backs to it, and push.

Their crazy strides are chopped in little steps.

And all their lives, like that, they'll have to rush

Forwards in reverse, always holding their caps.

from Barbarians, Faber, 1979.

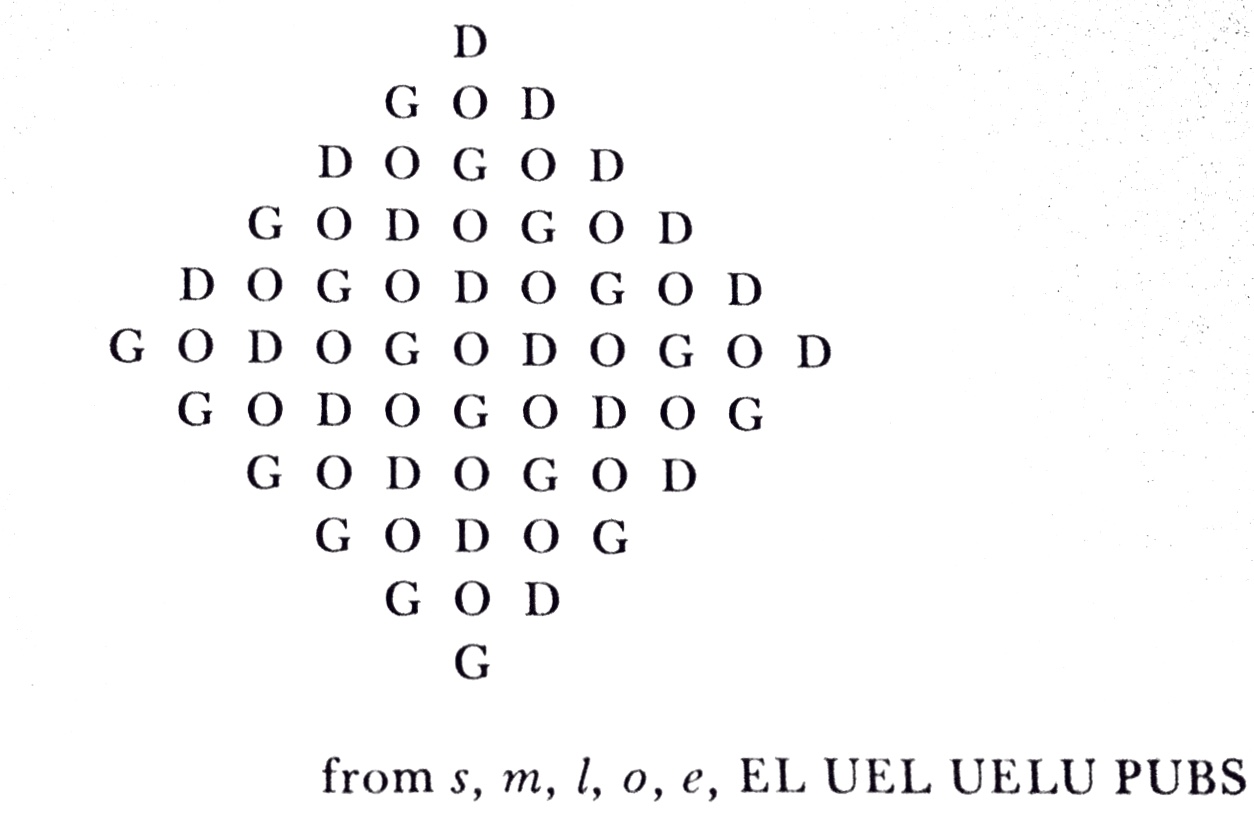

On the other hand, there is experimental poetry. One of its prime movers. Bob Cobbing, wrote in Krollok 2, 1971, that "It seems to me that almost all the valid experimental work going on at present in British poetry can conveniently be considered under the heading 'concrete' though I am aware that this is stretching the word concrete further than ever intended by the originators of the term 'concrete poetry'." Much of this concrete poets is impossible to illustrate here: indeed, at its extremes, genuine concrete poetry becomes graphic art, while sound poetry only lives in performance - when for example musicians are invited to perform texts. When it is possible to illustrate concrete poetry, as in the undated poem illustrated here by P. C. Fencott, it is as traditional as Dunn's poem quoted above.

The problem is to sift through the weight of paper between these poles for poems of high quality, and this cannot be done by excluding certain magazines or publishers a priori, since good things turn up in unexpected places. Much is clearly left to chance, as it would be an impossible task to keep track of everything. Although Geoffrey Grigson is right to criticise the prevalence of omnibus reviews for poetry - "If [a new book' is fit only for an inch or five inches in an omnibus review, it is fit for nothing and no one" (TLS, 8-1-80) -it is difficult to see how so much material could be reviewed otherwise. But, even so, he is only partly right. The whole reviewing structure is at fault inasmuch as it is geared to review names, when what is really needed is an attempt to review poems. When he states that "After looking and sifting and then repeating the process, my conviction is that since Eliot and the leading poets (now dead) of my own thirties generation, there have been no major poets, no “good" poets at all; and perhaps only six middling poets worth attending to - " he is perhaps close to the truth seen in the long term (certainly playing safe with posterity), but he neglects the important fact that major poems and -good- poems have been written, published and read regularly.

Denial of this would be mere arrogance, and this fact represents the sane point of reference from which a critic should work if he wishes to avoid monumental misjudgements such as F.R. Leavis's enthusiasm for Ronald Bottrall in New Bearings in English Poetry (1933, pp.201-211). Dr Leavis's error was to generate a significant poet from a few excellent lines of poetry. I believe that we should be modest, and content that there is good poetry to be enjoyed.

But the profusion of outlets for poetry increases the risk of over-rating a poet: a partisan press or magazine promotes a limited range of poets, who are given as much space as they desire for their work. They are tempted to over-produce, and necessarily vitiate their work. New little magazines burgeon with the explicit intent of avoiding this trap, but either fall instantly into it, or suffer from lack of clear purpose. The odd case of a recent magazine called Allusions will serve to illustrate how good intentions bring about the publication of bad poetry.

Allusions I costs forty pence, contains forty-eight roughly quarto pages and is published from the English Department of Manchester University. The editorial is typical in ambition, pretension and its slipshod writing: “Apart from established writers whose work is commercially published and widely read, there exist many whose work only appears in the little presses or in the printed outlets of local poetry groups who's work has yet to appear anywhere. Cultural barriers between these ‘catagories’ [sic] of writers lead to qualatitive [sic] judgements that are not always based on representing the work of established ‘names’ alongside the work of lesser known writers in the same magazine. Thus the work of Roger McGough, a well-established poet, Steve Sneyd, a stalwart of many littlepress magazines and Lupenga Mphande, of whom we know nothing, all appear with equal status in Allusions I." This seems to be a clear enough, and commendable, statement of intent, but on page 14 we find the following poem by Lupenga Mphande:

My home was eight miles to school,

Sometimes long after the noon gong

When my friends returned from dining

I'd just sit under a mango tree in

The school ground picking my teeth.

Is it a spoof? And, if not, what are the "valid criteria" for printing theses wishy-washy lines (that extraordinary floating preposition)? It is with relief that one turns to the saner reaches of Agenda, the PN Review and Stand, and other magazines of consistently high quality. Yet it is from this boscage that such peaks as Ted Hughes and Philip Larkin stand out, and it is this sub-culture of the poetry scene which creates the healthy statistical picture. One does not wish to doubt the sincerity of the editors of such magazines, but it is legitimate to ask whether they ultimately erode or enrich the poetry world. The long, quiet years of sacrifice by conscientious editors such as William Cookson, of Agenda, Martin Booth, of the Sceptre Press, and Norman Hidden, who manage miraculously to stand outside the fray, are mocked by silly typing errors and mis-placed critical enthusiasm. A potential reader of poetry, say a student, coming by chance upon an under-financed, poorly edited magazine or pamphlet might be permanently put off. But there are good things to be had on the fringe, such as this poem by Bob Cobbing:

Perhaps you can make sense out of this.

This make of can, you — perhaps — sense out.

This can make you out of sense, perhaps.

Out of this can, you make sense, perhaps.

This can of sense, you — perhaps — make out.

Out of 'perhaps' you can make this sense.

Make out this can of sense! (You perhaps,

Can make sense out of this. Perhaps you

Can.) Make out the 'you' of sense, perhaps.

You sense out, perhaps, this make of can.

Out of this can, you make sense, perhaps.

Can this sense of you, perhaps, make out?

Can you make sense, perhaps, out of this

Make of can? You sense out, perhaps, this

'You' out of this can. Make sense, perhaps,

Out of this! Make sense, perhaps, you can!

Out of this, you can, perhaps, make sense.

from Grin, Writers Forum, 1979

It is not to everybody's taste, but the humour is refreshing, and it is salutary to recall Pound's dictum that "gloom and solemnity are out of place in even the most rigorous study of an art originally intended to make glad the heal of man" in ABC of Reading, Faber edition, 1951, p.13). Furthermore this little booklet of Cobbing's is remarkable value at 10p for 26 page compared with, say, £4.95 for 87 pages of poetry by Maureen Duffy in Memorials of the Quick and the Dead (Hamish Hamilton, 1979).

A final problem involved in working through this vast spectrum of activity lies in the poets' own readings, and the atmosphere of the readings. At recent reading by Tom Pickard and Ken Smith, for instance, several good poems were sacrificed to the necessity of producing a show, sub specie Ginsberg — perhaps because the reading was being filmed by a television crew. In what had seemed to me from repeated reading a moving and rhythmically interesting poem created out of the personal suffering involved in Pickard's marriage to a Polish artist, a measured beery carelessness swamped the very qualities I had expected with dull, flat vowels. The poem is called Vis-a-vis Visa:

this pattern

we must learn

to live with

& love

each other

our days together

measured in advance

and stamped

but they

might learn

from us

and soon

as we

this day

delighted dance

our own

and altogether

other tune

from Hero Dust, Allison & Busby, 1979

After the weighty sadness of lines 6-8, and the efficaciously arresting verb "stamped", he turns the poem towards optimism, and I waited to hear the lift of the second syllable of "delighted":

as we

this day

delighted dance

and the marvellous closing lines of the poem. But the lift did not come; the voice droned on, and faded away rather than ending the poem. It was this that John Wain was referring to when he wrote that "Verbal nuance and literary allusion are rejected as elitist" (Professing Poetry, p.29).

But verbal magic is not elitist, and will not be drowned out by bitter beer and cigarettes. Fortunately the charm of the poetry itself, what the Arabs call its lawful magic, resolves the problems hinted at above. The patient reader is rewarded by phrases and rhythms which leap from the page and entrance him. That is the justification of the poet's trade, which I shall try to illustrate with a few recent examples.

It is a long and difficult leap to the austere technical excellence of Geoffrey Hill, and the perfection of his credo:

“…the problem for a poet who does believe in the essentially simple, sensuous and passionate nature of poetry but who is quite rightly sceptical of some of the more recent manifestations of confessionalism, is the problem of how to avoid debasing these concepts. And the way that he must do this is, I think, by an extreme concentration on technical discipline. In the climate of our time the very concentration on form and discipline is going to seem to a lot of people to be cold and cerebral. But I see it as the only true way of releasing the simple, sensuous and passionate.”

(interview in the New Statesman, 8 February 1980).

Although this credo has been manifest in his poems from the beginning, and informs such stunning achievements as the sonnet sequence ‘Funeral Music’ in King Log (1968), it is interesting to see the wording of this statement reflected in a recent poem, ‘A Short History of British India’ (III), in his latest volume Tenebrae (Andre Deutsch, 1978). This poem shows a superbly controlled, taut, felt, sense of history. The resonant names of the first line, echoing Villon: the exquisitely positioned and repeated verb ‘gone', unworldly images such as that of the names rising "like outcrops": these precise elements contribute to a haunting evocation of a vanished world in a style that vindicates Hill's views above in being simultaneously disciplined and passionate. I quote the whole poem:

Malcolm and Frere, Colebrook and Elphinstone,

the life of empire like the life of mind

'simple, sensuous, passionate', attuned

to the clear theme of justice and order, gone.

Gone the ascetic pastimes, the Persian

scholarship. the wild boar run to the ground,

the watercolours of the sun and wind.

Names rise like outcrops on the rich terrain,

like carapaces of the Mughal tombs

lop-sided in the rice fields, boarded-up

near railway sidings and small aerodromes.

'India's a peacock-shrine next to a shop

selling mangola, sitars, lucky charms,

heavenly Buddhas smiling in their sleep.'

His short, quiet poem on Bonhoeffer is another example:

Bonhoeffer in his skylit cell

bleached by the flares' candescent fall,

pacing out his own citadel.

restores the broken themes of praise,

encourages our borrowed days,

by logic of his sacrifice.

Against wild reasons of the state

his words are quiet but not too quiet.

We hear too late or not too late.

Whilst considering the coldness which many readers claim to feel in Hill's poems, John Bayley, after asking whether the “payoff” of this poem ‘is a little too carefully calculated to be wholly moving” , is forced to conclude that it could only have been written by a “very talented and original poet” (See ‘A Retreat or Seclusion’, in Agenda, Geoffrey Hill Special Issue, Spring, 1979).1979). There is now no doubt about Geoffrey Hill's stature; when his sensuality and passionate sincerity are fully understood he will be seen to mock Geoffrey Grigson's lament for the lack of a major poet, as a careful reading (aloud) of his ‘Funeral Music’ sequence will show, and I hope these two poems will have suggested.

‘Poem for Breathing’ by George MacBeth (Sceptre Press, 1979) is another quiet, forceful achievement by a poet showing a new assurance in a poem which involves the reader. It begins:

Trudging through drifts along the hedge, we

Probe at the flecked, white essence with sticks. Across

The hill field, mushroom-brown in

The sun, the mass of the sheep trundle

As though on small wheels. With a jerk, the farmer

Speaks, quietly pleased. Here's one. And we

Hunch round while he digs. Dry snow flies like castor

Sugar from the jabbing edge

Of the spade. The head rubs clear first, a

Yellow cone with eyes. The farmer leans, panting,

and continues through seven beautifully modulated stanzas. The precision of imagery is miraculous. When a sheep is discovered, and hoisted up:

Ten dark little

Pellets of shit steam in the hole,

Another sheep is discovered, and the lines:

The

Rush to see, the leaning sense of hush,

convey perfectly the hopes and fears of the entire search. But it is the conclusion that is most interesting, a consummate resolution which points the narrative content of the poem and brings the reader into intimate contact with the bleak landscape:

I crouch above the sheep, hunched in its

Briar bunk below the hedge. From the field, it

Hears the bleat of its friends, their

Far joy. It feels only the cushions

Of frost on its frozen back. I breathe, slowly,

Trying to melt that hard-packed snow. I

Breathe. melting a lstik snou,with my breath. If

Everyone in the whole

World would breathe here, a might help. Breathe

here a little, as you read, it might still help.

A satisfying and moving poem, reinforcing the tenacity of life in its optimism.

One of the most successful recent collections was Seamus Heaney's Life Work (Faber, 1979). Of its thirty poems one seems to me perfect, and a testimony to Emerson's remark that it is a "metre-making argument" rather than metre which makes a poem. It is called ‘The Harvest Bow’.

As you plaited the harvest bow

You implicated the mellowed silence in you

In wheat that does not rust

But brightens as it tightens twist by twist

Into a knowable corona.

A throwaway love-knot of straw.

Hands that aged round ashplants and cane sticks

And lapped the spurs on a lifetime of game cocks

Harked to their gift and worked with fine intent

Until your fingers moved somnambulant:

I tell and finger it like braille,

Gleaning the unsaid off the palpable,

And if I spy into its golden loops

I see us walk between the railway slopes

Into an evening of long grass and midges,

Blue smoke straight up, old beds and ploughs in hedges,

An auction notice on an outhouse wall —

You with a harvest bow in your lapel,

Me with my fishing rod, already homesick

For the big lift of these evenings, as your stick

Whacking the tips of weeds and bushes

Beats out of time, and beats, but flushes

Nothing: that original townland

Still tongue-tied in the straw tied by your hand.

The end of art is peace

Could be the motto of this frail device

That I have pinned up on our deal dresser —

Like a drawn snare

Slipped lately by the spirit of the corn

Yet burnished by its passage, and still warm.

As Harold Bloom has remarked, "Heaney could not have found a more wistful, Clare-like emblem than the love-knot of straw for this precariously beautiful poem" (TLS, Feb 8th, 1980). From the marvellous swirling rhythm of the first stanza, as it builds itself up into the love-knot,

But brightens as it tightens twist by twist

to the calmly achieved peace and warmth of the final stanza, this unusual eulogy on married love is triumphant. As Heaney distances himself from specifically Irish poems his gift is allowed the scope it requires, and he produces "major" poems such as this. It can stand without further comment as a poem of the first rank.

A final example of what I take to be a major work is Ted Hughes' poem ‘You Hated Spain’ (Poetry Supplement, Christmas 1979, The Poetry Book Society). In a deeply personal and powerful poem he reflects on his honeymoon with Sylvia Plath. It opens:

Spain frightened you. Spain

Where I felt at home. The blood-raw light,

The oiled anchovy faces, the African

Black edges to everything, frightened you.

Your schooling had somehow neglected Spain.

and develops with tragic intensity and a series of chilling images:

Bosch

held out a spidery hand and.you took it

Timidly, a bobby-sox American.

You saw right down the Goya grin

And recognised it, and recoiled

As your poems winced into chill, as y.our panic

Clutched back towards college America.

It is a rich and rewarding insight into a remarkable marriage, a glimpse into a private world terrifying after Heaney's calm — a poem charged by this extra tension into an even greater achievement. At its conclusion, we are left with the haunting image of Sylvia Plath, waiting "Like a soul waiting for a ferry", a delirious vision of happiness:

I see you, in moonlight,

Walking the empty wharf at Alicante

Like a soul waiting for a ferry,

A new soul, still not understanding,

Thinking it is still your honeymoon

In the happy world, with your whole life waiting,

Happy, and all your poems still to be found.

These varying levels of intensity, in Hill, MacBeth, Heaney and Hughes, demonstrate a hard-earned technical excellence which we must not expect too soon in the younger poets. But I am confident that others will break through, and that hope is sufficient to keep looking, reading. waiting. For the moment, I believe the poems quoted from these four writers will stand alone as evidence of the high quality of poetry today. As Geoffrey Hill wrote in his ‘September Song’ (in King Log):

This is plenty. This is more than enough.

'Poetry in England Today', Pacific Moana Quarterly, Vol. 6, No. 1, January 1981, pp.5-13.